Many of you have heard our griping about finding proper axe handles to hang on our axes. Given the amount of time we spend wailing and gnashing our teeth about axe handles we thought we should at least give the subject of handles its due.

In these posts we will explore the anatomy of the handle, the wood used to make them, the importance of grain orientation, handle shape, wedges, and finally the eternal debate of whether to use a secondary metal wedge or not.

Haft or Handle

The first controversy to sort out is what to call the thing that’s attached to the axe head? While we usually refer to it as a “handle” it is also called a “haft.” Haft comes from “helve” or “halve” which finds its roots in the Old English hielfe itself related to the Old Saxon word hèlvi. Of course, this being English we use haft and handle interchangeably and as both a noun and verb. Bonus!

Shoulder & Knob

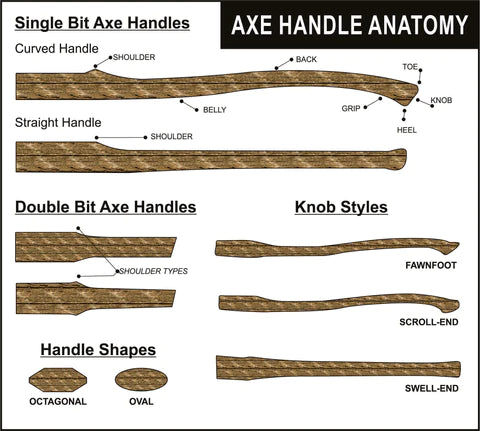

The two most prominent parts of an axe handle are the shoulder and the knob. The shoulder is wider than the rest of the handle against which rests the axe head. The shoulder is what stops the axe head from sliding down the handle.

A double bit handle will have a shoulder on both top and bottom. There are several types of knob ends of which the most common are the swell-end or fawn’s foot.

What are axe handles made from?

The most common wood used to make axe handles is American Hickory. Hickory is used due to its combination of strength and flexibility. Its strength allows it to take massive shocks without splitting or cracking. Tennessee Hickory Products has a nice video on its website explaining why this wood is preferred for tool handles. You can watch the video here.

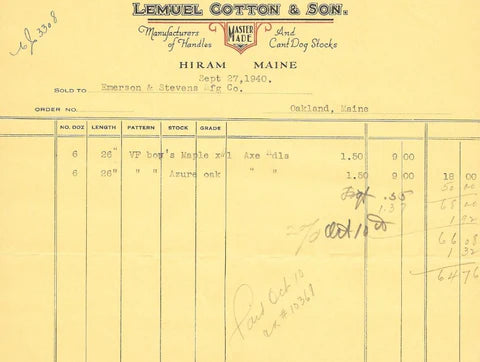

Other woods used for axe handles include ash, hop-hornbeam (aka ironwood), maple, and white oak. Since Maine does not have a wealth of hickory handle makers in the Pine Tree State had to use what was available. The Jacquith Handle Company of Clinton, Maine made their handles out of rock maple. Lemuel Cotton and his family used white oak and maple to make handles in his shop in Hiram, Maine from the 1870’s to the 1940’s.

[The reference to "azure oak" by Cotton is another story altogether!]

In addition to the species of wood used for handles there is also a question of whether to use the heartwood or sapwood of the tree. Heartwood consists of the older, darker center of the tree. Sapwood is its younger counterpart closer to the bark.

Over the years there has grown a prejudice against using heartwood in axe handles. It is thought to be more brittle than the softer sapwood. In second growth timber, this difference is not borne out from tests performed by the Forest Products Laboratory of U.S. Department of Agriculture. Hickory sapwood, heartwood or a combination of the two all make a fine axe handle.

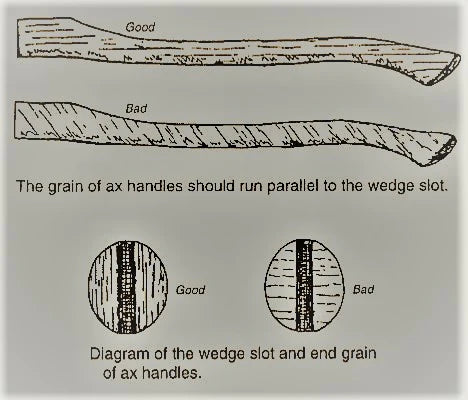

Axe Handle Grain

Another consideration when choosing a handle is the grain orientation. The grain of the handle should run parallel to the wedge slot. If the handle is cross-grained it is subject to splitting.

Most of the handles that are found commercially in your local hardware stores are what we politely refer to as “cross-grained cr%p.”

Here’s a poor old cross-grained handle that split right along the grain:

Another consideration when picking an axe handle is to make sure that there are no knots or checking in the handle which also reduces strength. Choose your handles carefully and if you see a straight grained, knot free handle – BUY IT!

Straight Axe Handles vs. Curved Axe Handles

At the most basic level there are straight axe handles and curved axe handles. In his Ax Book, Dudley Cook relates that during the Colonial period there were only straight axe handles. Around 1840, curved handles for single bit axes started to appear. The curved handle may have come to prominence because people simply liked how they looked. Whatever the reason curved single bit axe handles are now the standard. There is quite a bit of debate over the efficiency of using a single bit axe with a curved handle. Dudley Cook argues in the Ax Book, using detailed drawings and mathematical formulae, that a curved handle is less accurate for serious chopping. Others view this as baloney.

Double bit axes almost always have a straight handle. The exception is the long out of date curved Adirondack double bit handle. Used predominantly in the Adirondack region of New York the curved double bit handle is a bit of a mystery. One thing is sure though – it certainly adds a graceful touch to a menacing looking double bit axe!

Knob Ends & Shape of the Barrel

The other two differentiating characteristics of axe handles are the knob ends and the shape of the barrel of the handle.

The knob ends are either a sharp angled “fawn’s foot,” a more rounded version of a fawn’s foot referred to as a scroll end or a “swell end “reminiscent of a small knob on a baseball bat. Whatever the style the knob end allows the hand to slide down the handle without slipping off. Finally, the barrels of most handles are an oval shape. Occasionally you will see double bit handles that have been shaped into an octagonal pattern.

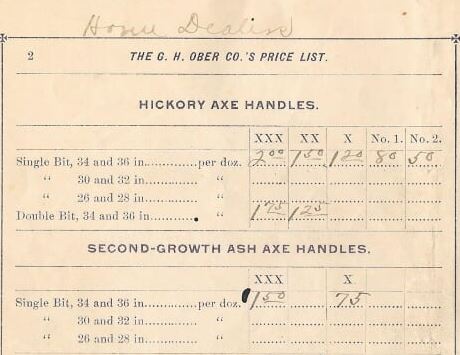

The length of the handle depends on the size of the axe head and the type of chopping you are going to do. Single bit axe handles range from 20” – 42.” A common size for large trees of Pacific NW was 42”. Smaller trees found in the Northeast were cut with axes handled at around 32" with 36” being more standard size in the rest of the country. Double bit axes can come in sizes from 28” to 42” with the more standard sizes being 34” and 36.”

Below are the different length handles offered by the Ober Company of Chagrin Falls, Ohio in 1894:

Axe Handle Wedge

When buying replacement axe handles, you will see a cut into the end of the handle where the axe head is to be fixed. This kerf cut is to insert the wooden wedge which expands the handle material against the eye of the axe head ensuring a tight fit.

The wood used in axe wedges is also a matter of debate. Some prefer hardwood wedges like oak as they are easier to put into the kerf cut; others like soft wood wedges like poplar or pine that absorb moisture and theoretically keep the handle tighter.

When looking at an axe you may notice a metal wedge (or two) put diagonally across the wooden wedge. The need for this is argued back and forth by axe enthusiasts.

One school of thought (Dudley Cook in his Ax Book adheres to this view) is that the metal wedge is necessary. Bernie Weisgerber in his manual published by the U.S. Forest Service An Ax To Grind argues vehemently against a secondary wedge: “The metal wedges tend to split the grain on the hickory handle. I can’t see any reason why you would want to do that to a properly hung ax.” [We here at B&C agree with Bernie and don’t add a secondary metal wedge when hafting our axes].

We hope that this post has provided some ammunition for arguing with your friends about the various aspects of axe handles from the wood used to their shape and how to wedge them. After all, what’s better than arguing about axes?!